Lessons in governance from "The Rest is Politics" podcast

If electoral representation is so broken, what's the fix?

“PEOPLE HATE politicians. What has the worst approval ratings in America, continuously? Congress … [That’s why] Donald Trump, in not sounding like a politician … actually manages … to win over a certain number of people.”

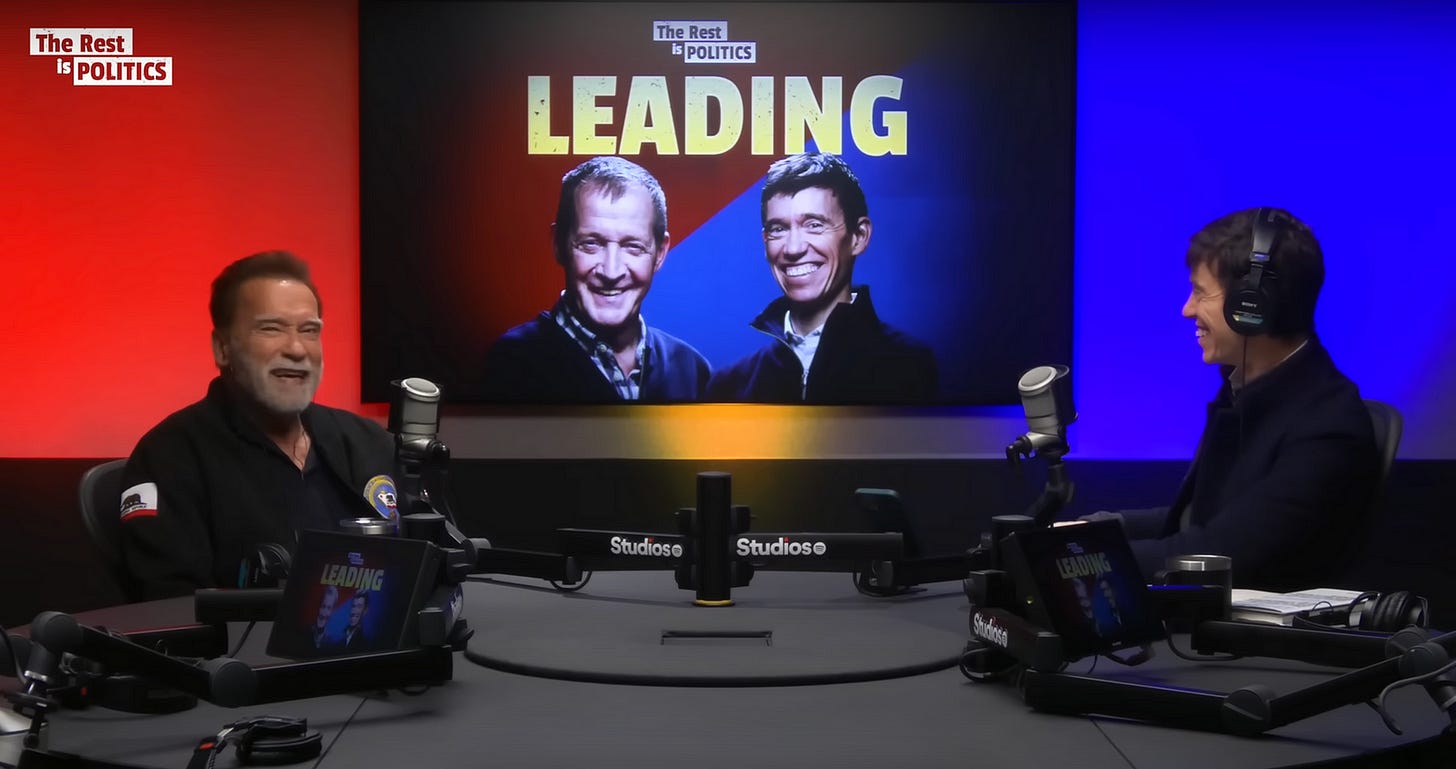

This kind of throwaway insight is typical of what has made me — and millions of others — an addict of The Rest is Politics podcast. I have learned so much from the presenters and guests. In the UK, they include communications guru Alastair Campbell and writer-politician Rory Stewart. The US branch is led by financier Anthony Scaramucci, a former pro-Trump political activist, and reporter Katty Kay (who said the above in episode #33).

But after two years, hundreds of episodes and more than two thousand kilometers — I listen while I run — I keep wondering about an inherent ambivalence in the shows.

In short, I feel that these cutting-edge experts and their world leader guests are not teaching me about what makes the political world go round. They are talking about what’s blocking it from getting anywhere at all.

Put another way, the heart of the shows is an insiders’ account of high politics. But at best, the elected governments of the world’s richer countries come across as lost in transition. The deeper the podcasts dive, the more these electoral systems seem to be in trouble. Fundamental reform seems urgently needed. Or maybe a transplant.

In the article below, I’ve put together examples of how The Rest is Politics describes this collapse of national and even global governance.

I do so in the hope these leading lights of our age will draw more conclusions when their analysis shows how broken the current system of electoral representation is, as well as to share with other listeners a new way of learning from these excellent podcasts too.

Crying out for change

To my ears, the drumbeat of the presenters’ critique sounds compelling. Political parties are selfish and dysfunctional. Most lawmakers have little or no knowledge of the laws they vote on. Some leaders may begin their careers with good intentions, but the system empowers charismatic me-first types and then puts impossible strain on people who make it to the top. Few if any politicians have enough time, authority or energy to fulfil their tasks effectively.

The presenters are aware of the irony that the kings in their parade of global events may be wearing no clothes.

“I do think there is something fundamentally wrong with our politics,” Campbell put it once (episode #163). “It’s partly what gave us Brexit. It’s partly what gave us this succession of pretty useless prime ministers. And it’s partly what’s making people frustrated that the Labour Party is not coming in with that sense of real … radical change that the country is crying out for.”

Yet the podcasters’ chorus line remains traditional: if only we try harder, if only we tweak things here or there, if only we find somebody better, we can make the existing system work.

And so I go on listening, hour after hour, to the apparently doomed political intrigues of people who are struggling — and failing — to do just that.

Since there is so much wisdom and so many good intentions in these podcasts — even among the politicians who appear on it — it is fair to ask: what is their conclusion, the essential core of their message about what can change?

Flirting with reform

Campbell and Stewart occasionally flirt with reforms or alternative ways of getting the right decision makers into power.

Both agree on doing something about the UK’s upper chamber of parliament, the House of Lords. Both talk much about using more proportional representation and transferring more power to the lower House of Commons. Both also like the sound of randomly selected citizens’ assemblies, if only in a sort of opinion-polling capacity.

Campbell recognizes the problem. ”There is a paradox,” he says (episode #299). “We are having more and more elections, more and more people voting, but we are not necessarily a more democratic world.”

But they do not seriously discuss options for going ahead with any of these, let alone back any firm, specific plan.

There’s been a noticeable drop in discussion of alternatives, for instance, since July when Sir Keir Starmer and his Labour Party were elected in the UK. It’s not the first time. Campbell remembers (episode #180) a plan to introduce proportional representation being much discussed by his Labour Party before their 1997 election victory. “Once we got into power,” he said, “that sort of went on to the back burner.”

The podcasters’ unwillingness to take their rich experience of political dysfunction to a logical conclusion also applies to their books published this year.

Campbell’s But What Can I Do? recognizes a population discouraged by their elected leaders’ poor performance. He talks much about the frustrated potential energy he feels in his contacts with the public, especially the young. He wants to channel this willingness to engage into political activity.

But — judging by what he says on the podcast — this is simply asking them to throw themselves into the same system of pointless political trench warfare that he says demotivated them in the first place.

Stewart’s Politics on the Edge powerfully describes the toxicity of his decade in the UK parliament and government. To improve the situation, he suggests more checks and balances, more transparency, better lobbying regulations, civic education, more judicial independence and new ways for parties to select parliamentary candidates.

But these praiseworthy ideas would treat the symptoms rather than the cause that is now hard baked into the system: the demands made on parties and politicians doomed to fight eternal elections. The damaging results include short-term policies that fail, rising unpopularity and their current crisis of lost authority.

In the US, with its more optimistic streak, Kay and Scaramucci go less far down this road. As they roll their eyes at politicians’ behaviour and detail public disappointment, they occasionally look back into history for insights and explanations, even re-reading texts by the US founding fathers. But I can’t remember them questioning the system itself or suggesting fundamental changes.

Really hollow

One of the gravest problems that emerges from my take on the podcasts is the role of political parties in the existing parliament.

“Something about the way that party politics works in the House of Commons has really meant that debates and scrutiny of legislation is almost meaningless today,” Stewart says (episode #206). “The Commons feels really hollow,”

A year before, Stewart had gone ever further (episode #140), citing a civil servant telling him that “the House of Commons was a complete waste of time, never bothered to look at the detail, never scrutinised anything.”

Stewart’s account of his own career in politics makes clear why those elected don’t bother to engage. A minister is simply not allowed to oppose a law backed by their party, and if they do, they are dismissed from office; any ordinary MP that does the same will never leave the backbenches.

A weird sect

One of their guests went further (episode #86 of Leading, a companion podcast to The Rest is Politics). Nick Clegg describes the three “bubbles” of his career: Brussels, where he was a member of the European Parliament, the UK parliament, where he was Liberal Party leader and deputy prime minister, and his current Silicon Valley job working for Meta (Facebook).

“Of those three bubbles, the worst by a long shot is [the UK Houses of Parliament in] Westminster,” he says. It’s “stuck in the 19th century … architecturally designed for conflict not conversation … like a weird sect … a pastiche of a Harry Potter boarding school.”

This prompts Stewart to slam “the incredible poor quality of so much of it … I was on the Foreign Affairs Committee and chaired the Defence Committee … we knew almost nothing about the world … we didn’t really hold ministers to account … speeches in parliament were of such pathetically low quality … nobody [was] paying the slightest attention … [the government was free to act] like an elected dictatorship.”

In other episodes Stewart points out how members of parliament have no job description (episode #224). He often notes how impossible it was to balance of his work as a constituency MP and that of representing the national interest as a foreign office minister by, say, travelling to the places affected by any policies. His book excoriates politicians as “grotesquely unqualified”.

For his part, Campbell points out there is no external audit of parliament, like, for instance, the never-ending inspections endured by Britain’s schools. Before the 2024 UK elections, Campbell (episode #180) goes as far as to say that “radical fundamental change” is needed, that he is “on a journey” on this topic and that the Labour Party manifesto should be offering what he called an “electoral review”.

Yet none of the podcasters ever stop to imagine a future that simply does away with the political parties that both rule and corrupt the system.

Sleepless in London, penniless in Paris

Two leaders who join the program describe an environment that gives little hope that an impeccable new leader will somehow get elected and miraculously sweep the problem away.

“It is widely underrated that politicians need to be made of very stern [stuff],” Clegg underlined (episode #87, Leading). “You’re taking most decisions, highly consequential decisions, often at very great speed, based on imperfect information, with very great consequences, in a sleepless state … We create a whole cast (and caste) of decision makers who are in a state which is the worst state in which to take decisions. They’re knackered.”

Former President François Hollande of France tells listeners (episode #69, Leading) that the new generation is simply not interested in coming to the rescue.

“Nobody in the elite wants to make politics. When I was a student, the main [idea of] success was to be a member of parliament, perhaps minister and if possible president. Now in the elite, politics is considered the wrong way. Now people want to be on boards, economic circles. Not in politics,” Hollande says. “It is hard in politics. You [face intrusions] on your private life, you do not have any revenues and wages in comparison with business. You can be defeated in elections. You have no holidays, no weekends, never. Why be committed? … Social media is harsh, cruel… in France, the political system is broken.”

Exposing the rottenness

So what is the alternative, and who will come together to find it? Probably not the politicians, or at least not yet.

Film star and ex-governor of California Arnold Schwarzenegger cites Albert Einstein to the podcasters (episode #43): “The same mind that created the problem is not able to solve it.” Another problem is what historian Dominic Sandbrook observes on a sister podcast (episode #35, The Rest is History): “To be a politician is to be divisive.”

Stewart and Campbell spend more time discussing the problem than the causes, and even worry that they are being too critical.

Campbell (episode #168) says he agrees with a lot of the negativity in Stewart book, but adds that “I worry that your basic message is that “politics is all terrible”.”

Stewart retorts that “I do believe that in order to change you’ve got to begin by really delving into the problems, we’ve got to expose where the rottenness is … we have had a mafia code of silence around parliament for a long time.”

An unshakeable faith in elections is the clear motor driving the dysfunctional system of parties, politicians and polarisation that they describe. But none of the podcasters question the idea — which only evolved in the 19th century — that voting is where democracy begins and ends.

CItizens’ assemblies

Despite their faith in the legitimacy of elections, however, Campbell and Stewart have at times been ready to toy with fundamentally different approaches. This was especially evident at the peak of their frustration in the final months of the Conservative Party’s time in power in the UK from 2010–2024.

Stewart in particular finds much to like in one potentially radical alternative: citizens’ assemblies. These are groups of citizens from a community or country, randomly selected by lot, a process also called sortition. Participants meet over several days to learn from experts, deliberate and propose solutions to a common policy problem.

“I am very attracted by sortition, the basis of how juries are selected, and it’s how ancient Athens worked,” Stewart said (episode #173). “I am very interested in what happens if you do it from the whole public … a genuinely representative sample of people … This would take power away from parties, which I like.”

Campbell is the more reserved of the pair — saying only “we both think they are a good idea” (episode #224) — but Stewart is enthusiastic. At one point (episode #199) he said citizens’ assemblies are “the most exciting thing that’s facing democracies around the world.”

Stewart praises random selection as a way of getting a wide range of points of view working on an idea (episode #173). Later he points out (episode #269) that: “Real truth emerges quite slowly through giving people space and time to debate and explore ideas. Maybe change their opinion a little bit.”

Even so, for both Campbell and Stewart, such assemblies can only work in an advisory capacity, or, in Stewart’s case, possibly as a third British House of Citizens alongside the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

Taking the people into account

One notable guest, economist Kate Raworth, firmly advocated the use of citizens’ assemblies as the way forward. She did so in answer to Campbell’s lament that China’s dictatorial capitalism is getting ahead of “democracies with very, very short timeframes” (Leading episode #22).

“Many politicians will say: “I know what I need to do, I just don’t know how to get reelected when I’ve done it”,” Raworth responded. “That’s why you’re seeing some of the most progressive places say: “Let’s hold a citizens assembly, use sortition. Let’s bring together a randomly selected group of around 100 citizens, residents of our place. Let’s introduce them to experts who can introduce them to the scale of the topic and see what they come up with. Time and again, what’s coming out of these citizens’ assemblies is that these people — who are not trying to get reelected, because they are citizens thinking of the long view — have come up with far more ambitious policies than politicians feel they are able to.”

When Campbell worries that these policies might not be implemented, Raworth rises to the challenge, pointing out that what’s needed is for governments to commit to “taking into account what the people of this nation are saying they want to happen.”

That would be a wonderful development indeed. But the podcasters changed the subject back to economic growth. As usual, they fail to take their analysis to the logical conclusion that a new democratic system is needed.

Reflecting later in the episode on their conversation with Raworth, Campbell recognized that “our current politics” made him feel impotent to make any of her “idealistic” suggestions come about. He added: “The only way to you’re actually going to do this is if you live in a dictatorship.”

Shaken to the core

The Raworth interview is not the only time that The Rest is Politics podcasters note that the conclusion that some people are drawing from the mess they describe is not a desire to see bottom-up democracy like citizens' assemblies, but more top-down, authoritarian rule.

So which is it to be? How much time do the richer world’s governments have to find an alternative to their current dead end? Who will lead the way?

Former UK deputy prime minister Nick Clegg opined (episode #87, Leading) that: “I find myself more of an anti-establishment politician after five years in government than before … There’s so much that needs to be shaken to the core.”

Yet, as so many top establishment politicians before him, Clegg has been rewarded at Meta with a lucrative job at the pinnacle of the existing system. Normally, this is one way that rich companies control parties and politicians, who need money and support to win elections.

Unusually, though, Meta is both part of the problem, as its algorithms tear down the old order — whether empowering individual access to information or feeding polarisation—and offering possible solutions, as it experiments in sortition-based online deliberation within its global community of billions. But again, we hear nothing about that.

Back in the UK, “it could not be clearer that people don’t just think that the country’s stuck. They think politics is part of the problem,” Campbell proclaims (episode #154). “If it’s a part of the problem, you have to change it.”

But what should that change be? Perhaps only a new podcast series called The Rest is Democracy could fully answer the question. My running shoes are ready.